Henryk Hektor Siemiradzki (24 October 1843 – 23 August 1902) was a Polish painter, best remembered for his monumental Academic art. He was particularly known for his depictions of scenes from the ancient Graeco-Roman world and the New Testament, owned by national galleries of Poland, Russia and Ukraine.

Many of his paintings depict scenes from antiquity, often the sunlit pastoral scenes or compositions presenting the lives of early Christians. He also painted biblical and historical scenes, landscapes, and portraits. His best-known works include monumental curtains for the Lviv Theatre of Opera and for the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków.

The graceful, almost unintentionally elegant poses and gestures of the figures, the subtle gradations of the pure, saturated colours and above all the picturesqueness of the landscapes filled with air and sunlight, these elements render Siemiradzki’s idyllic scenes charming... More

Christ goes to the house of a woman named Martha. Her sister, Mary, sat at his feet and listened to him speak. Martha, on the other hand, went to "make all the preparations that had to be made". Upset that Mary did not help her, she complained to Christ to which he responded: "Martha, Martha, ... you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her." More

The Jewish attitude towards Samaritans is faithfully reflected in the New Testament, especially in Jesus' controversial choice of a "good Samaritan" to attack over-pious Jewish practices (Luke 10:30-37). Matthew is hostile to Samaritans; Mark ignores them altogether, and Luke keeps his distance. John is more radical, as the story of Jesus and the Samaritan Woman shows.

Kupala Night, also known as Ivan Kupala Day (Feast of St. John the Baptist), is celebrated in Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, Baltic countries and Russia currently on the night of 6/7 July in the Gregorian or New Style calendar, which is 23/24 June in the Julian or Old Style calendar still used by many Orthodox Churches. In Poland it is celebrated on the night of 23/24 June. Calendar-wise, it is opposite to the winter holiday Koliada. The celebration relates to the summer solstice when nights are the shortest and includes a number of Slavic rituals.

Many of the rites related to this holiday within Slavic religious beliefs, due to the ancient Kupala rites, are connected with the role of water in fertility and ritual purification.

On Kupala day, young people jump over the flames of bonfires in a ritual test of bravery and faith. The failure of a couple in love to complete the jump while holding hands is a sign of their destined separation. More

Siemiradzki was born to a Polish noble family of an officer of the Imperial Russian Army, Hipolit Siemiradzki, and Michalina, in the village of Bilhorod, or Novobelgorod, near the city of Kharkov in the Russian Empire, where his father's regiment was stationed. The family had origins in Radom land and derived its name from the village of Siemiradz. One of the branches settled in the late 17th century near Navahrudak. Henryk's grandfather held the post of podkomorzy (Chamberlain) in Nowogródek powiat.

The Varangians or Varyags was the name given by Greeks and East Slavs to Vikings, who, between the 9th and 11th centuries, ruled the medieval state of Kievan Rus' and formed the Byzantine Varangian Guard. According to the 12th century Kievan Primary Chronicle, a group of Varangians known as the Rus' settled in Novgorod in 862 under the leadership of Rurik. Before Rurik, the Rus' might have ruled an earlier hypothetical polity. Rurik's relative Oleg conquered Kiev in 882 and established the state of Kievan Rus', which was later ruled by Rurik's descendants. More

The Polish painter Henryk Siemiradzki painted the funeral ritual of Vikings in what is now Russia, in accordance with descriptions by Ahmad ibn Fadlan:

"They are the filthiest of all Allah’s creatures: they do not purify themselves after excreting or urinating or wash themselves when in a state of ritual impurity after coitus and do not even wash their hands after food.

In the case of a rich man's funeral, they gather together his possessions and divide them into three portions, one third for his household, one third with which to cut funeral garments for him, and one third with which they ferment alcohol which they drink on the day when his slave-girl kills herself and is burned together with her master". More

His parents were close friends with Adam Mickiewicz's family. He studied at Kharkov Gymnasium where he first learned painting under the local school teacher, D.I. Besperchy, former student of Karl Briullov. He entered the Physics-Mathematics School of Kharkov University and studied natural sciences there with great interest, but also continued to paint.

Depicting Nero watching how a captive Christian woman is killed in a re-enactment of the Greek myth of Dirce.

Dirce was the wife of Lycus, in Greek mythology, and aunt to Antiope whom Zeus impregnated. Antiope fled in shame to King Epopeus of Sicyon, but was brought back by Lycus through force, giving birth to the twins Amphion and Zethus on the way. Dirce hated Antiope and treated her cruelly after Lycus gave Antiope to her; until Antiope, in time, escaped.

In Euripides' lost play Antiope, Antiope flees back to the cave where Amphion and Zethus were born, now living there as young men. They disbelieve her claim to be their mother and refuse her pleas for sanctuary, but when Dirce comes to find Antiope and orders her to be killed, the twins are convinced by the shepherd who raised them that Antiope is their mother. They kill Dirce by tying her to the horns of a bull.

Dirce was devoted to the god Dionysus. He caused a spring to flow where she died, either at Mount Cithaeron or at Thebes, and it was a local tradition for the outgoing Theban hipparch to swear in his successor at her tomb. More

Saints Timothy and Maura suffered for the faith during the time of persecution under the emperor Diocletian (284-305). Saint Timothy came from the village of Perapa (Egyptian Thebaid), and was the son of a priest by the name of Pikolpossos. He was made a reader among the church clergy and likewise a keeper and copyist of Divine-service books. Saint Timothy came under denunciation that he was a keeper of Christian books, which by order of the emperor were to be confiscated and burned. They brought Saint Timothy before the governor Arian, who demanded him to hand over the clergy books. For his refusal to obey the command, they subjected the saint to horrible tortures. They shoved into his ears two red-hot iron rods, from which the sufferer lost his eyesight and became blind. Saint Timothy bravely endured the pain and he gave thanks to God, for granting him to suffer for Him. The torturers hung up the saint head downwards, putting in his mouth a piece of wood, and they tied an heavy stone to his neck. The suffering of Saint Timothy was so extreme, that the very ones executing the torment began to implore the governor to ease up on the torture. And about this time they informed Arian, that Timothy had a young wife by the name of Maura, whom he had married a mere 20 days before. Arian gave orders to bring Maura, hoping, that with her present they could break the will of the martyr. At the request of Maura, they removed the piece of wood from the mouth of the martyr, so that he could speak. Saint Timothy urged his wife not to be afraid of the tortures and to go the path with him. Saint Maura answered: "I am prepared to die with thee", – and boldly she confessed herself a Christian. Arian gave orders to tear out the hair from her head and to cut off the fingers from her hands. Saint Maura with joy underwent the torment and even thanked the governor for the torture, suffered in the redemption of sins. Then Arian gave orders to throw Saint Maura into a boiling cauldron, but she did not sense any pain and she remained unharmed. Suspecting that the servants out of sympathy for the martyress had filled the cauldron with cold water, Arian went up and ordered the saint to splash him on the hand with water from the cauldron. When the martyr did this, Arian screamed with pain and drew back his scaulded hand. Then, momentarily admitting the power of the miracle, Arian confessed God in Whom Maura believed as the True God, and he gave orders to release the saint. But the devil still held great power over the governor, and soon he again began to urge Saint Maura to offer sacrifice to the pagan gods. Having gotten nowhere, Arian was overcome all the more by a satanic rage and he began to come up with new tortures. Then the people began to murmur and demand a stop to the abuse of this innocent woman. But Saint Maura, turning to the people, said: "Let no one defend me, I have one Defender – God, on Whom I trust".

Finally, after long torments Arian gave orders to crucify the martyrs. Over the course of ten days they hung on crosses face to face with each other.

On the tenth day of martyrdom the saints offered up their souls to the Lord. This occurred in the year 286. Afterwards at Constantinople there began solemn celebration of the memory of the holy Martyrs Timothy and Maura, and a church was built in their honour. More

After graduating from the University with the degree of Kandidat (a first post-graduate scientific degree) he abandoned his scientific career and moved to Saint Petersburg to study painting at the Imperial Academy of Arts in the years 1864–1870. Upon his graduation he was awarded a gold medal. In 1870–1871 he studied under Karl von Piloty in Munich on a grant from the Academy. In 1872 he moved to Rome and with time, built a studio there on Via Gaeta, while spending summers at his estate in Strzałkowo near Częstochowa in Poland.

Phryne's real name was Mnēsarétē ("commemorating virtue"), but owing to her yellowish complexion she was called Phrýnē ("toad"). This was a nickname frequently given to other courtesans and prostitutes as well. The exact dates of her birth and death are unknown, but she was born about 371 BC. In that year Thebes razed Thespiae not long after the battle of Leuctra and expelled its inhabitants. More

In 1873 he received the title of Academician of the Imperial Academy of Arts for his painting Christ and a Sinner, based on a verse from Tolstoy. In 1878 he received the French National Order of the Legion of Honour and a Gold Medal of the Paris World's fair for the painting Flower vase. In 1876–1879 Siemiradzki worked on frescoes for the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (Moscow) among his other large-scale projects.

Nero’s Torches is arguably the most important work to have been produced by Henryk Siemiradzki. The artist’s own pride for his original version of the subject became apparent when, in 1879, he chose to present it as a gift to the city of Krakow (this donation initiated the collection of paintings of the National Gallery of Krakow. Siemiradzki’s Torches is still catalogued as number 1 in the Gallery’s inventory). Few other versions by Siemiradzki himself are known or traceable today. Copies of the painting by other artists - contemporary and posthumous - have been recorded ever since the painting was publicly exhibited. More

He died in Strzałkowo in 1902 and was buried originally in Warsaw, but later his remains were moved to the national Pantheon on Skałka in Kraków.

Acknowledgement: Wikipedia,

Images are copyright of their respective owners, assignees or others

Christ and Sinner, c. 1875

Oil on canvas

350 × 550 cm (137.8 × 216.5 in)

The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ and Sinner, c. 1875

The First Meeting of Christ and Mary Magdalene

Left Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ and Sinner, c. 1875

The First Meeting of Christ and Mary Magdalene

Center Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ and Sinner, c. 1875

The First Meeting of Christ and Mary Magdalene

Right Detail

Many of his paintings depict scenes from antiquity, often the sunlit pastoral scenes or compositions presenting the lives of early Christians. He also painted biblical and historical scenes, landscapes, and portraits. His best-known works include monumental curtains for the Lviv Theatre of Opera and for the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, c. 1886

Oil on canvas

Christ goes to the house of a woman named Martha. Her sister, Mary, sat at his feet and listened to him speak. Martha, on the other hand, went to "make all the preparations that had to be made". Upset that Mary did not help her, she complained to Christ to which he responded: "Martha, Martha, ... you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her." More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ and Samaritan woman, c. 1890

Oil on canvas

106.5 × 184 cm (41.9 × 72.4 in)

Lviv National Art Gallery, Ukraine

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ and Samaritan woman, c. 1890

Detail, Left Side

Christ and Samaritan woman, c. 1890

Detail, Left Side

In the Gospel of John, Jesus revealed himself for the first time as “I Am” to a woman that rabbinic law forbade him to interact with. He met her by Jacob’s well in the Samarian town called Sychar, where he had come to rest on his journey from Judea to Galilea, his body weary and thirsty from traveling. As he watched her fill her pitcher with water from the earth, he asked, “would you give me a drink?”.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ and Samaritan woman, c. 1890

Detail, Right Side

The woman, seeing he was a Jew, took an untrusting step backward, distancing herself from this stranger who addressed her so casually. “How is it that you, a Jew, are speaking to me, a woman from Samaria?”. In response, Jesus did not speak, but he returned her gaze with kind eyes and wordlessly stretched his hand toward her, showing his desire to receive a drink. With a hesitant sharpness in her voice, she doubts him again: “And you are asking me, a woman, for a drink?”

To this, Jesus replied compassionately, “If you knew the gift of God and who it is that asks you for a drink, you would have asked him and he would have given you living water” More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ blessing the children, 1900

Oil on canvas

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christ blessing the children, 1900

Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Night on the Eve of Ivan Kupala, c. 1892

Oil on Canvas

Lviv National Art Gallery, Ukraine

Kupala Night, also known as Ivan Kupala Day (Feast of St. John the Baptist), is celebrated in Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, Baltic countries and Russia currently on the night of 6/7 July in the Gregorian or New Style calendar, which is 23/24 June in the Julian or Old Style calendar still used by many Orthodox Churches. In Poland it is celebrated on the night of 23/24 June. Calendar-wise, it is opposite to the winter holiday Koliada. The celebration relates to the summer solstice when nights are the shortest and includes a number of Slavic rituals.

Many of the rites related to this holiday within Slavic religious beliefs, due to the ancient Kupala rites, are connected with the role of water in fertility and ritual purification.

On Kupala day, young people jump over the flames of bonfires in a ritual test of bravery and faith. The failure of a couple in love to complete the jump while holding hands is a sign of their destined separation. More

Siemiradzki was born to a Polish noble family of an officer of the Imperial Russian Army, Hipolit Siemiradzki, and Michalina, in the village of Bilhorod, or Novobelgorod, near the city of Kharkov in the Russian Empire, where his father's regiment was stationed. The family had origins in Radom land and derived its name from the village of Siemiradz. One of the branches settled in the late 17th century near Navahrudak. Henryk's grandfather held the post of podkomorzy (Chamberlain) in Nowogródek powiat.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Funeral of a Rus' nobleman, Burial of a Varangian Chieftain, 1883

State Historical Museum

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Funeral of a Rus' nobleman, Burial of a Varangian Chieftain, 1883

Detail. Left Side

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Funeral of a Rus' nobleman, Burial of a Varangian Chieftain, 1883

Detail. Right Side

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Funeral of a Rus' nobleman, Burial of a Varangian Chieftain, 1883

The Polish painter Henryk Siemiradzki painted the funeral ritual of Vikings in what is now Russia, in accordance with descriptions by Ahmad ibn Fadlan:

"They are the filthiest of all Allah’s creatures: they do not purify themselves after excreting or urinating or wash themselves when in a state of ritual impurity after coitus and do not even wash their hands after food.

In the case of a rich man's funeral, they gather together his possessions and divide them into three portions, one third for his household, one third with which to cut funeral garments for him, and one third with which they ferment alcohol which they drink on the day when his slave-girl kills herself and is burned together with her master". More

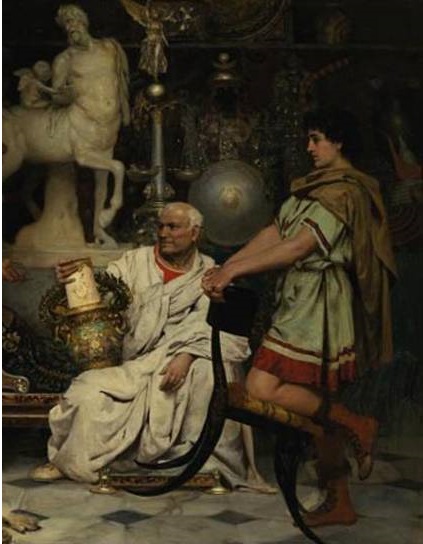

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

The patrician's siesta, c. 1881

Oil on canvas

79.4 × 127.6 cm (31.3 × 50.2 in)

Contra Costa Hospice in California

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

A Dangerous Game, c. 1880

Oil on canvas

Henryk Siemiradzki

The Judgment of Paris, c. 1892

Oil on canvas

99 x 227 cm

National Museum, Warsaw

Henryk Siemiradzki

The Judgment of Paris, c. 1892

Detail, Left

Henryk Siemiradzki

The Judgment of Paris, c. 1892

Detail, Center

Henryk Siemiradzki

The Judgment of Paris, c. 1892

Detail, Right

Three goddesses claimed the apple: Hera, Athena and Aphrodite. They asked Zeus to judge which of them was fairest, and eventually he, reluctant to favor any claim himself, declared that Paris, a Trojan mortal, would judge their cases. More

His parents were close friends with Adam Mickiewicz's family. He studied at Kharkov Gymnasium where he first learned painting under the local school teacher, D.I. Besperchy, former student of Karl Briullov. He entered the Physics-Mathematics School of Kharkov University and studied natural sciences there with great interest, but also continued to paint.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christian Dirce, c. 1897

Oil on canvas

263 × 530 cm (103.5 × 208.7 in)

National Museum in Warsaw, Poland

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Christian Dirce, c. 1897, Detail

Oil on canvas

263 × 530 cm (103.5 × 208.7 in)

National Museum in Warsaw, Poland

Dirce was the wife of Lycus, in Greek mythology, and aunt to Antiope whom Zeus impregnated. Antiope fled in shame to King Epopeus of Sicyon, but was brought back by Lycus through force, giving birth to the twins Amphion and Zethus on the way. Dirce hated Antiope and treated her cruelly after Lycus gave Antiope to her; until Antiope, in time, escaped.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

The Sketch Of Christian Dirce, c. 1896

Dirce was devoted to the god Dionysus. He caused a spring to flow where she died, either at Mount Cithaeron or at Thebes, and it was a local tradition for the outgoing Theban hipparch to swear in his successor at her tomb. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Martyrdom of Saints Timothy and Maura, c. 1885

Oil on canvas

125 × 200 cm (49.2 × 78.7 in)

National Museum in Warsaw

Finally, after long torments Arian gave orders to crucify the martyrs. Over the course of ten days they hung on crosses face to face with each other.

On the tenth day of martyrdom the saints offered up their souls to the Lord. This occurred in the year 286. Afterwards at Constantinople there began solemn celebration of the memory of the holy Martyrs Timothy and Maura, and a church was built in their honour. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Martyrdom of Saints Timothy and Maura, c. 1885

Detail, Left

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Martyrdom of Saints Timothy and Maura, c. 1885

Detail, Right

After graduating from the University with the degree of Kandidat (a first post-graduate scientific degree) he abandoned his scientific career and moved to Saint Petersburg to study painting at the Imperial Academy of Arts in the years 1864–1870. Upon his graduation he was awarded a gold medal. In 1870–1871 he studied under Karl von Piloty in Munich on a grant from the Academy. In 1872 he moved to Rome and with time, built a studio there on Via Gaeta, while spending summers at his estate in Strzałkowo near Częstochowa in Poland.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Phryne at the Poseidonia in Eleusis, c. 1889

Oil on canvas

State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, Russia

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Phryne at the Poseidonia in Eleusis, c. 1889

Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Phryne at the Poseidonia in Eleusis, c. 1889

Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Roman Orgy In The Time Of Caesars, 1872

Oil on canvas

The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Ancient Romans prudery was to the highest degree -- couples had sex at night, in complete darkness, and with most of their clothes on. Sure, wealthy Romans had sex in front of their servants, but to them house servants were like furniture that could bring you stuff.

It appears that the stories of Roman sex festivals were mostly the result of nasty rumors made up after the fact. Early Christian proselytizers knew their audience, and nothing stirs up the blood of an entire culture of super-prudes like the idea that somewhere, someone is having sex differently from everybody else. So, to promote their nascent religion to the Roman masses, early Christian writers crafted lurid tales of debauchery that were happening -- but only at those rich houses. In a culture that celebrated solemnity and virtue, nothing defamed the traditional religion of the day like being associated with well-lit nudity and sex parties. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Roman Orgy In The Time Of Caesars, 1872

Detail, Right

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Roman Orgy In The Time Of Caesars, 1872

Detail, Left

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

ORGY ON CAPRI IN THE TIME OF TIBERIUS, 1881

13.39 X 27.56 in (34 X 70 cm)

Oil on canvas

In 26 AD, twelve years into his reign, Tiberius withdrew to the island of Capri, never to return to the Rome. Once on Capri, Tiberius ‘finally gave in to all the vices he had struggled so long to conceal’. His drinking was legendary, his sex life exceeded the worst imaginings. Surrounded by sexually explicit art-works, Tiberius was addicted to every kind of perversion, with boys, girls – even tiny children. The accusations relating to oral sex would have aroused particular loathing on the part of Roman readers. Tiberius’ appetites were hardly human; ‘people talked of the old goat’s den – making a play on the name of the island’. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

ORGY ON CAPRI IN THE TIME OF TIBERIUS, 1881

Detail, Right

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

ORGY ON CAPRI IN THE TIME OF TIBERIUS, 1881

Detail, Left

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Dance amongst swords, c. 1881

Oil on canvas

120 × 225 cm (47.2 × 88.6 in)

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Also known as Dance Amongst Daggers, Dance Amongst Swords and similar variations. It depicts a nude woman who dances between swords while a group of women play music and a few men watch. The setting is Italian and there have been several interpretations of what exactly the painting depicts.

Siemiradzki made four versions of the painting, each with a slightly different composition and colour scheme. One of the versions, originally commissioned by K. T. Soldatenkov, is located at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Another version was sold at auction in 2011 for 2,098,500 dollars, which was the new record for a Siemiradzki painting. The record was held until 2013, when Un naufragé mendiant was sold for 1,082,500 pounds. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Dance amongst swords, c. 1881

Detail Left

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Dance amongst swords, c. 1881

Detail Right

In 1873 he received the title of Academician of the Imperial Academy of Arts for his painting Christ and a Sinner, based on a verse from Tolstoy. In 1878 he received the French National Order of the Legion of Honour and a Gold Medal of the Paris World's fair for the painting Flower vase. In 1876–1879 Siemiradzki worked on frescoes for the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (Moscow) among his other large-scale projects.

Nero's Torches (Christian Candlesticks), C. 1877

oil on canvas

305 × 704 cm (120.1 × 277.2 in)

National Museum, Kraków, Poland

Siemiradzki uses the immense canvas to present the theme of the persecution of early Christians by Nero. The emperor’s contemporaries accused him of setting fire to Rome in 64 AD. Fearing the consequences, the ruler blamed it all on Christians, who were very unpopular in the Roman society. The artist painted a scene with Christians being burnt alive in Nero’s gardens. A variety of feelings are visible on the faces of the onlookers, ranging from the wild bestiality of drunken Romans, through the cold indifference of the beautiful ladies and dashing young men, to fear and feel compassion for the alleged arsonists.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Nero's Torches (Christian Candlesticks), C. 1876

Left Detail

The artists modelled the reliefs and architectonic details visible in the painting on ancient relics preserved in Rome, Pompeii, and Naples, as well as on later works on ancient architecture.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Nero's Torches (Christian Candlesticks), C. 1876

Center Detail

As far as the ideology behind the canvass is concerned, the artist presented two groups of people: the Roman elite, mostly degenerated or intimidated by the despotic Nero, and the steadfast Christians ready to die for their faith. On the frame of the painting one can make out an inscription from Gospel according to St. John – Polish equivalent for: “And the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it”. It was mainly because of this inscription that the painting was seen as a metaphor for resistance against violence and the despotic rule of the tsar in Poland and Russia. It was a symbol of future victory of those who are now weak and held in contempt. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Nero's Torches (Christian Candlesticks), C. 1876

Right Detail

Nero’s Torches is arguably the most important work to have been produced by Henryk Siemiradzki. The artist’s own pride for his original version of the subject became apparent when, in 1879, he chose to present it as a gift to the city of Krakow (this donation initiated the collection of paintings of the National Gallery of Krakow. Siemiradzki’s Torches is still catalogued as number 1 in the Gallery’s inventory). Few other versions by Siemiradzki himself are known or traceable today. Copies of the painting by other artists - contemporary and posthumous - have been recorded ever since the painting was publicly exhibited. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Two figures at the statue of the Sphinx

(sketch for Lights of Christianity "Torches of Nero" picture)

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Lights of Christianity, Nero's Torches (Christian Candlesticks), C. 1876

Sketch

In 1879 he offered one of his best-known works, the enormous Pochodnie Nerona (Nero's torches), painted around 1876, to the newly formed Polish National Museum. The artwork is on display at the Siemiradzki Room of the Sukiennice Museum in the Kraków Old Town, the most popular branch of the museum today. Around 1893 Siemiradzki worked on two large paintings for the State Historical Museum (Moscow) and in 1894 produced his monumental curtain for the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków.Sketch

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

The Girl or the Vase?, c. 1878

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

The Girl or the Vase?, c. 1878

Detail, Right Side

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

The Girl or the Vase?, c. 1878

Detail, Left Side

He died in Strzałkowo in 1902 and was buried originally in Warsaw, but later his remains were moved to the national Pantheon on Skałka in Kraków.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

A Spring, c. 1898

Oil, canvas

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

A Spring, c. 1898

Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Warriors in the Battle of Silistria/ The Rape of the Sabine Women, c. 1867

54 x 76 cm (21½ x 30 in)

State Historical Museum, Moscow

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Warriors in the Battle of Silistria/ The Rape of the Sabine Women, c. 1867

Detail

In this drawing Henryk Siemiradzki has presented an intense and dramatic interpretation of the story of The Rape of the Sabine Women. The Rape (in this context, rape means abduction) is supposed to have occurred in the early history of Rome, not long after its foundation by Romulus. Romulus and his troops sought to find wives in order to start new families and ensure the future growth of the population.

In The Rape of the Sabine Women Siemiradzki has chosen to depict the frenzy of the abduction. The emotions of the various figures are plain to see; the determination of the Romans, the desperate defiance of the Sabine men, and the helpless anguish of the women. Every figure has been closely studied and individualised, so that the viewer becomes engrossed by the individual conflicts within the larger melee. More

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Barbarians in the ruined palace, (1890-1892)

Muzeum Narodowe w Karakowie

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Corsairs, c. 1880

Kharkov Art Museum, Kharkov, Ukraine

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Corsairs, c. 1880

Detail, Left

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Corsairs, c. 1880

Detail, Right

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Begging castaway, c. 1878

Oil on canvas

Height: 208 cm (81.9 in). Width: 293.5 cm (115.6 in)

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Begging castaway, c. 1878

Height: 27.5 cm (10.8 in). Width: 38.2 cm (15 in).

Galeria Sztuki, Lwów, Ukraina

Study

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Following the gods, c. 1899

Oil on canvas

75 × 120 cm (29.5 × 47.2 in)

Lviv National Art Gallery

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

With viaticum, c. 1889

Oil on canvas

60 × 130 cm (23.6 × 51.2 in)

National Museum in Warsaw

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

With viaticum, c. 1889

Detail

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

With Consolation and Relief, c. 1885

Oil on canvas

57 x 119 cm

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

With Consolation and Relief, c. 1885

Detail, Right

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

With Consolation and Relief, c. 1885

Detail, Left

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902)

Reclining of models, c. 1881

Oil on wood

20 x 40 cm

Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Fine Arts

Acknowledgement: Wikipedia,

Images are copyright of their respective owners, assignees or others