Head of the God Osiris,

ca. 595-525 B.C.E.

Slate

7 7/8 x 4 3/4 in. (20 x 12 cm).

Brooklyn Museum

Osiris, one of Egypt’s most important deities, was god of the underworld. He also symbolized death, resurrection, and the cycle of Nile floods that Egypt relied on for agricultural fertility.

According to the myth, Osiris was a king of Egypt who was murdered and dismembered by his brother Seth. His wife, Isis, reassembled his body and resurrected him, allowing them to conceive a son, the god Horus. He was represented as a mummified king, wearing wrappings that left only the green skin of his hands and face exposed.

More on Osiris

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of ancient Egypt between about 2000 BC and 1700 BC, stretching from the establishment of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, although some writers include the Thirteenth and Fourteenth dynasties. During this period, Osiris became the most important deity in popular religion.

The period comprises two phases, the 11th Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes and the 12th Dynasty onwards which was centered on el-Lisht (located south of Cairo). These two dynasties were originally considered to be the full extent of this unified kingdom, but historians now consider the 13th Dynasty to at least partially belong to the Middle Kingdom

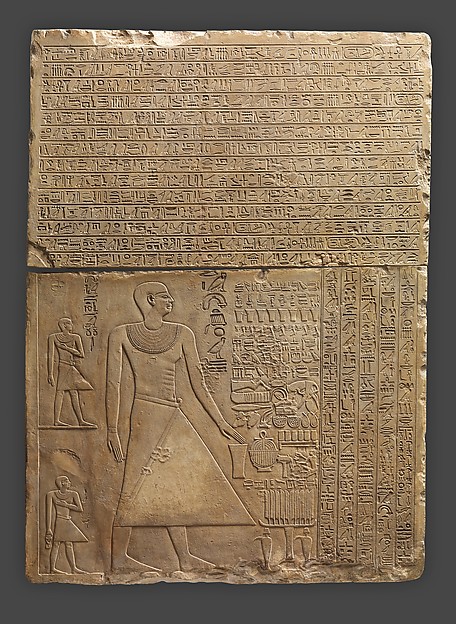

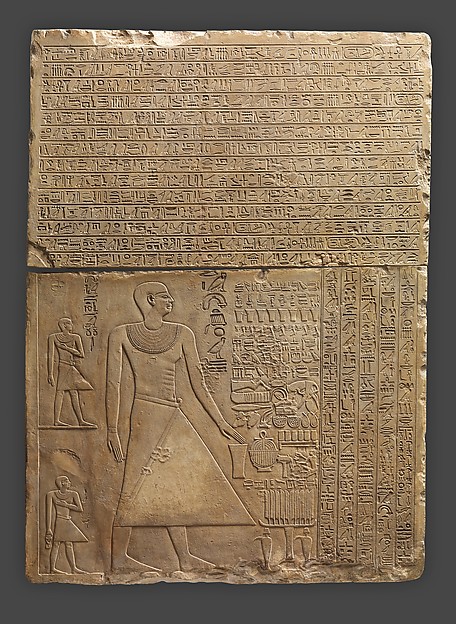

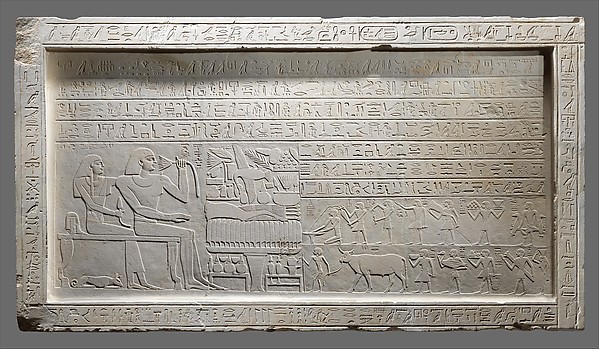

Stela of the Chief Treasurer and Royal Chamberlain Tjetji

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 11, ca. 2124-1981 B.C.

Egypt, Theban Region, Thebes

Limestone

58 1/4 × 43 1/2 × 18 11/16 in. (148 × 110.5 × 47.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The images on this stela show Tjetji receiving a wealth of offerings intended to sustain him in the afterlife. Characteristic of art at the dawn of the Middle Kingdom are the long stiff limbs, thick lips, and heavy cosmetic lines around the eyes. The extensive text on this stela describes events that took place during the reign of King Wahankh Intef II, under whom Tjetji served, just before the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. Intef II began the process of reunification by extending his rule over the eight southernmost nomes, or provinces, of Egypt. The text further relates the transition to the succeeding king, Nakhtnebtepnefer Intef III, under whom Tjetji proudly kept his former offices.

After the collapse of the Old Kingdom (Dynasties 3–6, ca. 2649–2150 B.C.), Egypt entered a period of weak Pharaonic power and decentralization called the First Intermediate Period. Towards the end of this period, two rival dynasties, known in Egyptology as the Tenth and Eleventh, fought for power over the entire country. The Theban 11th Dynasty only ruled southern Egypt from the first cataract (The 1st Cataract cuts through Aswan), to the Tenth Nome of Upper Egypt (Edfo). Its former location was selected for the construction of Aswan Low Dam, the first dam built across the Nile.to the Tenth Nome of Upper Egypt.

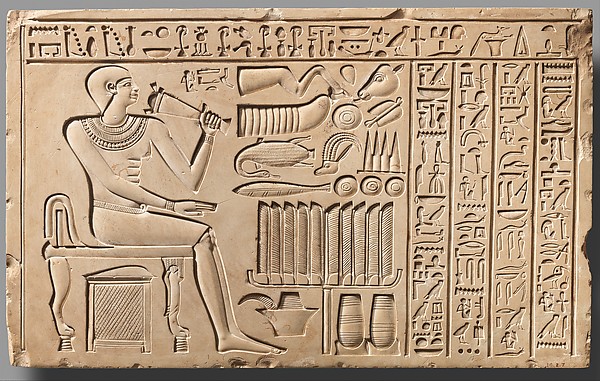

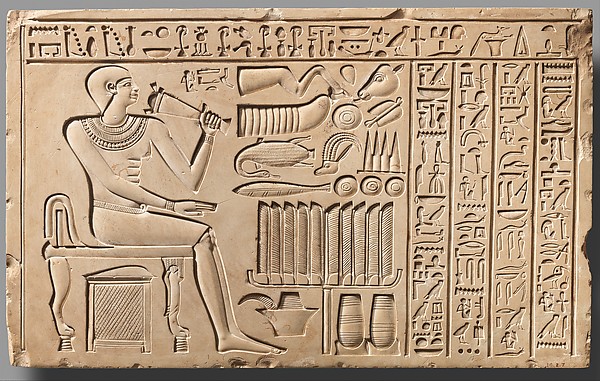

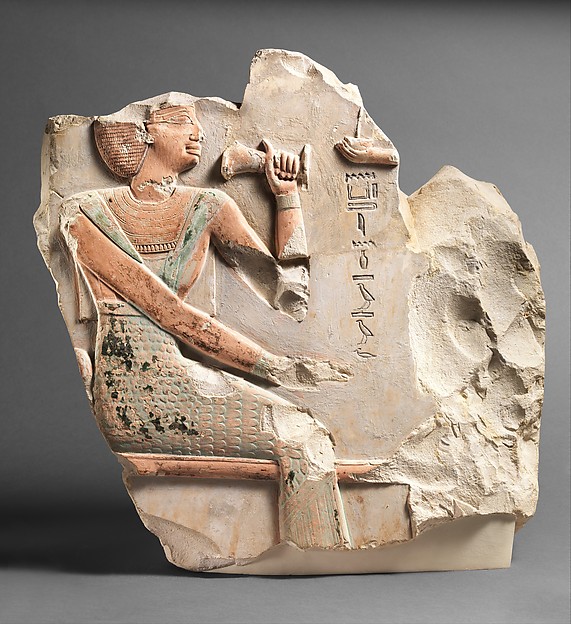

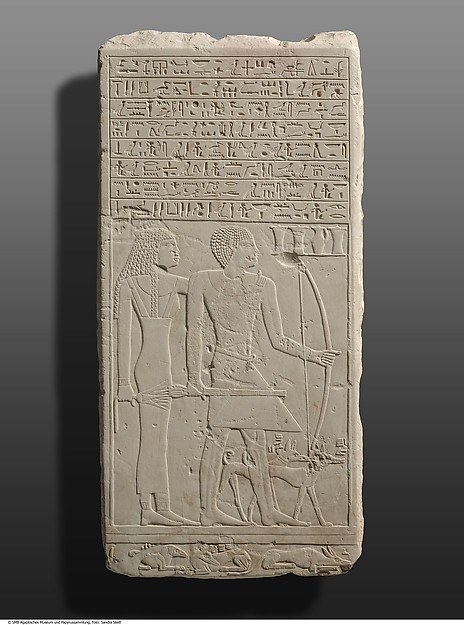

Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati

First Intermediate Period, Dynasty 11, reign of Mentuhotep II, early, ca. 2051–2030 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes; Probably from Tarif

L: 59 cm (23 1/4 in.), H: 36.3 cm (14 5/16 in.), D: 8 cm (3 1/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Maati is shown seated in front of the offering table with a jar for the sacred oil in his left hand. The text on this relief art contains references to other figures of the time-such as Maati's overseer, the treasurer Bebi, who later became a vizier, and an ancestor of the ruling family called Intef "the Great"-demonstrating the close ties that bound rulers and followers together in the Theban society of the time.

To the north, Lower Egypt was ruled by the rival 10th Dynasty from Herakleopolis (approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) west of the modern city of Beni Suef) The struggle was to be concluded by Mentuhotep II, who ascended the Theban throne in 2055 B.C. Mentuhotep II took advantage of a revolt in the Thinite Nome to launch an attack on Herakleopolis, and met little resistance. After toppling the last rulers of the 10th Dynasty, Mentuhotep began consolidating his power over all Egypt. For this reason, Mentuhotep II is regarded as the founder of the Middle Kingdom.

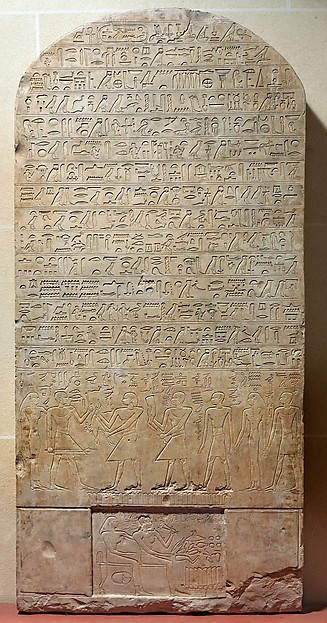

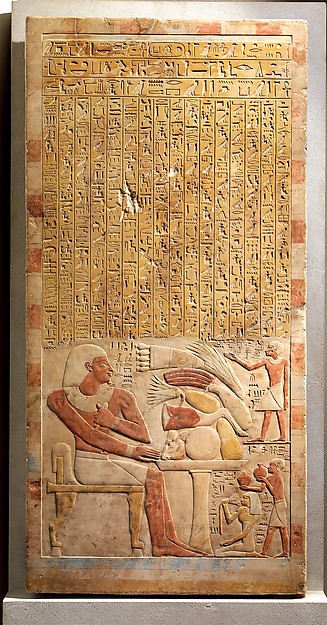

Stela of the Overseer of the Troops Intef

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11, ca. 2124-1981 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes

Limestone

H. 170 cm (66 15/16 in.); W. 116 cm (45 11/16 in.); D. 21 cm (8 1/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As overseer of the troops under Mentuhotep II, Intef must have been instrumental in the wars that resulted in the unification of the country during this king’s reign. His reward was an opulent tomb. The typical funerary scene depicts Intef seated before an offering table piled with food while receiving the homage of a son or brother. Below are funerary texts. The broad proportions of the well-muscled figure are typical of the middle of the Mentuhotep II era.

Mentuhotep II commanded military campaigns south as far as the Second Cataract in Nubia. He also restored Egyptian hegemony over the Sinai region, which had been lost to Egypt since the end of the Old Kingdom. To consolidate his authority, he restored the cult of the ruler, depicting himself as a god in his own lifetime, wearing the headdresses of Amun and Min. He died after a reign of 51 years, and passed the throne to his son, Mentuhotep III.

Stela of the Overseer of the Fortress Intef

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11, late, Mentuhotep II, ca. 2021–2000 B.C.

Egypt

Painted limestone

H. 78 cm ( 30 11/16 in); W. 142 cm (55 7/8 in); D. 7.5-8.5 cm (3-3 3/8 in)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

On its top ledge, this stela proclaims the name of King Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II (ca. 2051–2000 B.C.), the founder of the Middle Kingdom. In the same line, the stela's owner, Intef, refers to himself as "his (the king's) servant." Intef also recounts that he was overseer of a fortress and served in the region of Herakleopolis, the capital city of the minor kings who ruled northern Egypt before the country's reunification under Mentuhotep II. Mentuhotep II could only have appointed an official there after having eliminated the last of these rulers during his reunification of Egypt (around 2021 B.C.)

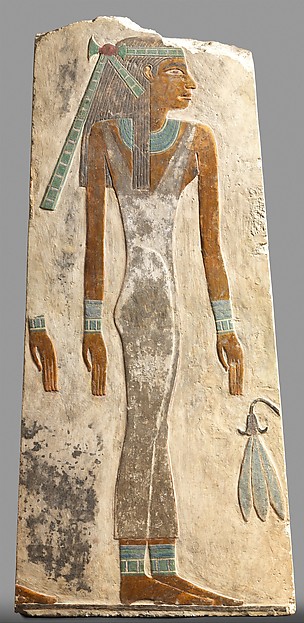

Relief of Seankhkare Mentuhotep III and the Goddess Iunyt

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11, Mentuhotep III, ca. 2000-1988 B.C.

Egypt, Armant

Limestone

H. 78.7 cm (31 in.); W. 134.6 cm (53 in.); D. 11.5 cm (4 1/2 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

On the right, King Seankhkare Mentuhotep III faces the goddess Iunyt, a consort of the war god Montu. On the left, the king wears the red crown of Lower Egypt and enacts a running ritual, probably in front of Montu. During the Eleventh Dynasty, many of the modest mud-brick Old Kingdom sanctuaries in Upper Egypt were replaced with superbly decorated limestone buildings, including the temple at Armant.

Mentuhotep III reigned for only twelve years, during which he continued consolidating Theban rule over the whole of Egypt, building a series of forts in the eastern Delta region to secure Egypt against threats from Asia. He also sent the first expedition to Punt during the Middle Kingdom, by means of ships constructed at the end of Wadi Hammamat, on the Red Sea.

Relief block with the names of Amenemhat I and Senwosret I

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Amenemhat I (coregency with Senwosret I), ca. 1962–1952 B.C.

Egypt, Memphite Region, Lisht North, Pyramid Temple of Amenemhat I, re-used in foundation, MMA excavations, 1908–09

Limestone

H. 37.5 cm (14 3/4 in.); W. 88.5 cm (34 13/16 in.); D. 13 cm (5 1/8 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

King Amenemhat I (left) wears a crown with tall feathers, while King Senwosret I (right) has a crown with ram’s horns, little of which survives. The relief was originally part of a block that separated two rooms in a temple dedicated to King Amenemhat I. In these scenes, he was shown as a living king addressed by his son Senwosret I, who was also depicted as a ruling pharaoh. The representations indicate a coregency, a new development in the Middle Kingdom.

Mentuhotep III was succeeded by Mentuhotep IV, whose name significantly is omitted from all ancient Egyptian king lists. The Turin Papyrus claims that after Mentuhotep III came "seven kingless years". Despite this absence, his reign is attested from a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat that record expeditions to the Red Sea coast and to quarry stone for the royal monuments. The leader of this expedition was his vizier Amenemhat, who is widely assumed to be the future pharaoh Amenemhet I, the first king of the 12th Dynasty.

Relief block with the names of Amenemhat I and Senwosret I

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Amenemhat I (coregency with Senwosret I), ca. 1962–1952 B.C.

Egypt, Memphite Region, Lisht North, Pyramid Temple of Amenemhat I, MMA excavations, 1908–09

Limestone

H. 37.5 cm (14 3/4 in.); W. 88.5 cm (34 13/16 in.); D. 13 cm (5 1/8 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Continued from above. On this relief, King Senwosret I’s name is on the left and King Amenemhat I’s on the right. King Amenemhat .I as a living king, addressed by his son Senwosret I, a ruling pharaoh.

Relief of Offering Bearers

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret I, ca. 1961–1917 B.C.

Egypt, Memphite Region, Lisht South, Pyramid Temple of Senwosret I, Sanctuary, south wall, MMA excavations, 1908–09

Limestone, paint

H. 146.2 cm (57 9/16 in.); W. 128.3 cm (50 1/2 in.); D. 14.6 cm (5 3/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

These heavily laden offering bearers are from the end of a procession of men bearing offerings to king Senwosret I. They are both high officials; their titles are inscribed above them. The one at the right, who carries papyrus and lotus flowers and birds in a cage, is a "high official, district administrator of Dep [Buto]"; the one at the left, who brings a platter of fruit and cooked poultry, is an "acquaintance of the palace." Another "district administrator," now lost, was once at the very right.

Mentuhotep IV's absence from the king lists has prompted the theory that Amenemhet I usurped his throne. While there are no contemporary accounts of this struggle, certain circumstantial evidence may point to the existence of a civil war at the end of the 11th dynasty. Inscriptions left by one Nehry, the Haty-a of Hermopolis, suggest that he was attacked at a place called Shedyet-sha by the forces of the reigning king, but his forces prevailed. Khnumhotep I, an official under Amenemhet I, claims to have participated in a flotilla of 20 ships to pacify Upper Egypt. What is certain is that, however he came to power, Amenemhet I was not of royal birth

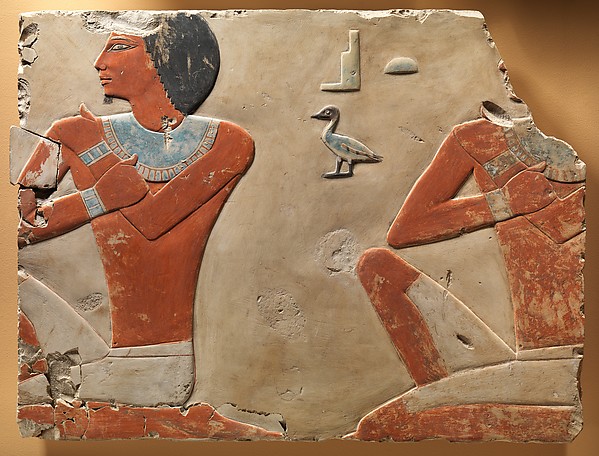

Relief of an Offering Bearer with Pintail Ducks

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, Reign: Amenemhat I,

ca. 1981-1952 B.C.

Egypt, Memphite Region, Lisht North

Limestone, paint

H. 45.7 cm (18 in.); W. 23.5 cm (9 1/4 in.); D. 6.4 cm (2 1/2 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Like the relief from the pyramid temple of Senwosret I, above, this piece also originates from a procession of offering bearers walking toward the king. In this case, the relief likely comes from a modest royal chapel attached to the north side of the pyramid of Amenemhat I. Here, a man removes ducks from a cage and slaughters them as a stage in the preparation of the king’s eternal meal. The offering bearer is shown with two left hands, an incongruity that allows for a more graphic depiction of the action. The low relief and delicate modeling are typical of the reign of Amenemhat I.

From the 12th dynasty onwards, pharaohs often kept well-trained standing armies, which included Nubian contingents. These formed the basis of larger forces which were raised for defence against invasion, or for expeditions up the Nile or across the Sinai. However, the Middle Kingdom was basically defensive in its military strategy, with fortifications built at the First Cataract of the Nile (Aswan), in the Delta and across the Sinai Isthmus.

Relief of an Elite Woman of the Provinces

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Reign of Senwosret III

ca. 1981-1802 B.C.

Egypt, El-Bersha, Tomb of Djehutyhotep (Tomb 2)

Limestone, paint

28 3/8 × 13 × 4 3/4 in. (72 × 33 × 12 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This lavishly attired, elegant woman belonged to a procession of family members attending the nomarch (regional governor) Djehutyhotep II. An identifying inscription has not survived, but she was likely a sister or daughter. The fine artistry of the relief attests to the wealth commanded by regional leaders during the first half of the Twelfth Dynasty. After that period, the office of nomarch died out and with it the richly painted tombs of the Middle Egypt region.

Early in his reign, Amenemhet I was compelled to campaign in the Delta region, which had not received as much attention as upper Egypt during the 11th Dynasty. In addition, he strengthened defenses between Egypt and Asia, building the Walls of the Ruler in the East Delta region. Perhaps in response to this perpetual unrest, Amenemhat I built a new capital for Egypt in the north, known as Amenemhet Itj Tawy, or Amenemhet, Seizer of the Two Lands.

Lintel of Amenemhat I and Deities

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Amenemhat I–Senwosret I, ca. 1981–1952 B.C.

Egypt, Memphite Region, Lisht North, Pyramid Temple of Amenemhat I, MMA excavations, 1907

Limestone, paint

H. 36.8 cm (14 1/2 in.); W. 172.7 cm (68 in.); D. 13.3 cm (5 1/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the relief King Amenemhat I is shown celebrating his thirty-year jubilee (Heb Sed). He is flanked by the gods Anubis with a jackal head (in front) and Horus with a falcon head (behind), both of whom offer him the ankh, or symbol of life. At the left of the block stands the goddess Nekhbet of Upper Egypt and on the right the goddess Wadjet of Lower Egypt. The king wears a tightly curled wig with the uraeus on his brow and the false beard of kingship. He carries the flail and a ceremonial instrument. The low-relief carving is delicate, but many details are only indicated in paint.

The location of this capital is unknown, but is presumably near the city's necropolis, the present-day el-Lisht (south of Cairo). Like Montuhotep II, Amenemhet bolstered his claim to authority with propaganda. In particular, the Prophecy of Neferty dates to about this time, which purports to be an oracle of an Old Kingdom priest, who predicts a king, Amenemhet I, arising from the far south of Egypt to restore the kingdom after centuries of chaos.

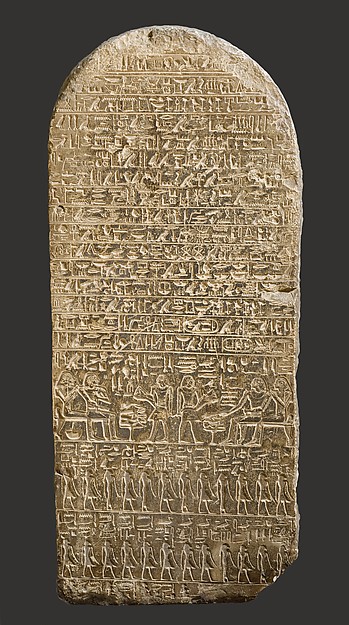

Stela of the Overseer of Artisans Irtisen

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2030-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Abydos

Limestone

46 1/4 × 22 1/16 in. (117.5 × 56 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Irtisen was an overseer of artisans, a profession that he praises on this stela, one of the most famous ancient Egyptian documents connected to artistic production. Placing himself among society’s elite, he describes his mastery of the secrets related to hieroglyphic writing, rituals, and magic. He further relates that he knows the poses and proportions of particular types of figures in sculpture and relief and the recipes used to create enduring colors. All this knowledge would be transmitted only to his eldest son. A standard funerary offering scene is depicted below, followed by a recessed shrine, the doors of which have been opened to reveal Irtisen and his wife seated at an offering table.

Propaganda notwithstanding, Amenemhet never held the absolute power commanded in theory by the Old Kingdom pharaohs. During the First Intermediate Period, the governors of the nomes of Egypt, nomarchs, gained considerable power. Their posts had become hereditary, and some nomarchs entered into marriage alliances with the nomarchs of neighboring nomes. To strengthen his position, Amenemhet required registration of land, modified nome borders, and appointed nomarchs directly when offices became vacant, but acquiesced to the nomarch system, probably in order to placate the nomarchs who supported his rule. This gave the Middle Kingdom a more feudal organization than Egypt had before or would have afterward.

Stela of the Overseer of Sculptors Shensetji

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12

Senwosret I

ca. 1961-1917 B.C.

Egypt; Said to be from Abydos

Limestone

35 × 15 in. (88.9 × 38.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Commemorative stela and tomb inscriptions of the Middle Kingdom sometimes include idealized biographies, providing information about historical events as well as individual lives. The text on the stela of Shensetji begins with the titulary of the pharaoh Senwosret I, under whom he served, and continues with standard funerary formulas. It concludes with a statement about Shensetji’s life: he was first a sculptor in the capital Itjtawi (Lisht) and later moved to Abydos, where he presumably helped to decorate the temple of the funerary god Osiris. The inscription provides important evidence that artists moved between key centers of production. The two seated couples receiving offerings are Shensetji and his wife (left) and probably his parents (right). Rows of family members stand below.

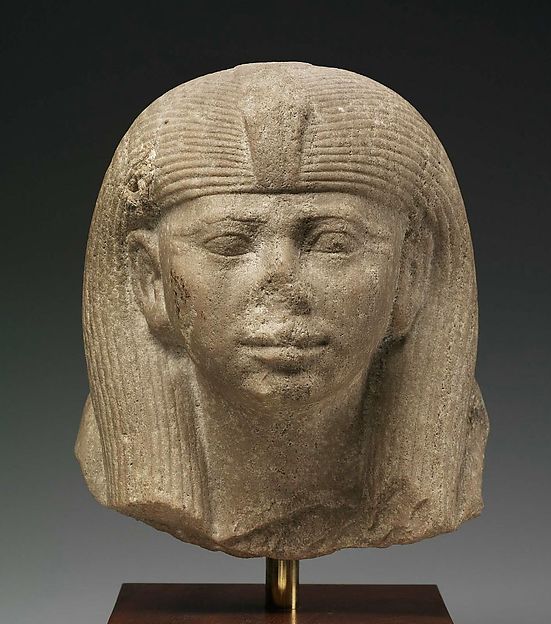

Head of a statue of king Senwosret I

12th dynasty

In his 20th regnal year, Amenemhat established his son Senusret I as his coregent, establishing a practice which would be used repeatedly throughout the rest of the Middle Kingdom and again during the New. In Amenemhet's 30th regnal year, he was presumably murdered in a palace conspiracy. Senusret, campaigning against Libyan invaders, rushed home to Itjtawy to prevent a takeover of the government.

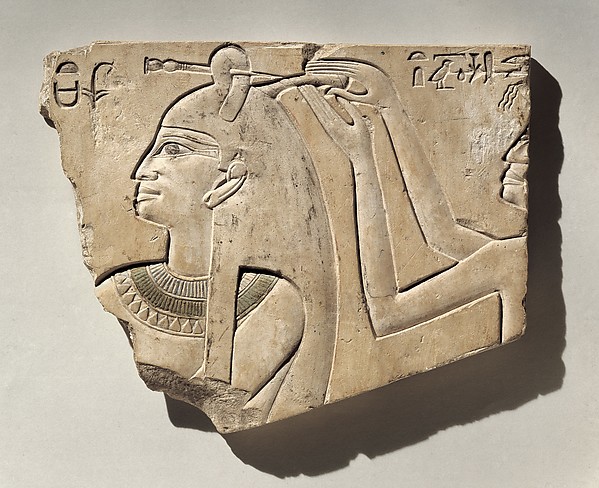

Relief of Queen Neferu Having Her Hair Done

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2051-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb of Neferu

Medium: Limestone, paint

H. 19 cm (7 1/2 in.); W. 23.6 cm (9 5/16 in.); D. 1.9 cm (3/4 in.)

Head of a statue of king Senwosret I

he Metropolitan Museum of Art

The entrance corridor of the queen’s tomb was probably decorated with sunk relief. This small fragment from an unusual hairdressing scene might have belonged to a ritual series in honor of Hathor, goddess of love and sexuality. The queen may have been depicted in purification rites enacted before she either took part in a Hathoric ceremony or perhaps even played the role of the goddess herself. The inscription above Neferu identifies her as a king’s wife, while that on the far right names the hairdresser, Henut.

During his reign he continued the practice of directly appointing nomarchs, and undercut the autonomy of local priesthoods by building at cult centers throughout Egypt. Under his rule, Egyptian armies pushed south into Nubia as far as the second cataract (Nubia is now submerged under Lake Nasser), building a border fort at Buhen and incorporating all of lower Nubia as an Egyptian colony. To the west, he consolidated his power over the Oases, and extended commercial contacts into Syrio-Palestine as far as Ugarit (what is now called Ras Shamra). In his 43rd regnal year, Senusret appointed Amenemhet II as junior coregent, and died in his 46th.

Relief of a Sunshade Bearer

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2051-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb of Neferu

Limestone, paint

7 11/16 × 5 1/8 in. (19.5 × 13 cm)

he Metropolitan Museum of Art

This woman carries a long wood pole ending in a stylized lotus bud, from which hangs a piece of cloth with red-orange stripes. When stretched, the cloth would have served as a shade against the blazing Egyptian sun. Neferu’s tomb featured a large number of sunshade bearers. Though no surviving inscriptions explain their significance, they seem to have been connected to the rituals enacted for the goddess Hathor, a prominent element of the decorative program of Neferu’s tomb.

The reign of Amenemhat II has been often characterized as largely peaceful, but record of his genut, or daybooks, have cast doubt on that assessment. Among these records, preserved on temple walls at Tod and Memphis, are descriptions of peace treaties with certain Syrio-Palestinian cities, and military conflict with others. To the south, Amenemhet sent a campaign through lower Nubia to inspect Wawat ( the land between the first and second cataracts). It does not appear that Amenemhet continued his predecessors' policy of appointing Nomarchs, but let it become hereditary again. Another expedition to Punt dates to his reign. In his 33rd regnal year, he appointed his son Senusret II coregent.

Relief of Clapping Women

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2051-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb of Neferu

Limestone, paint

H. 31.7 cm (12 1/2 in.); W. 27.9 cm (11 in.); D. 1.2 (1/2 in.)

he Metropolitan Museum of Art

This relief fragment depicts a row of clapping women with arms and hands upraised. It probably belonged to a larger scene of a ritual featuring singing or dancing in honor of the goddess Hathor, who was closely connected to these performances. Unusual are the strands of round beads in the women’s hair, which have no exact parallels. Perhaps they were connected with Hathoric rites of the time.

Evidence for military activity of any kind during the reign of Senusret II is non-existent. Senusret instead appears to have focused on domestic issues, particularly the irrigation of the Faiyum. This multi-generational project aimed to convert the Faiyum oasis into a productive swath of farmland. Senusret eventually placed his pyramid at the site of el-Lahun, near the junction of the Nile and the Fayuum's major irrigation canal, the Bahr Yussef. He reigned only fifteen years, which is evidenced by the incomplete nature of many of his constructions. His son Senusret III succeeded him.

Relief of offering bearers carrying boxes

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 11

Reign of Mentuhotep II, early

ca. 2051–2030 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb of Neferu (TT 319, MMA 31), MMA excavations, 1923–25

Limestone, paint

H. 21 cm (8 1/4 in.); W. 53 cm (20 7/8 in.); D. 8 cm (3 1/8 in.)

he Metropolitan Museum of Art

Chests with linen clothing played a prominent role in festivals honoring of Hathor. The presence of these fragments in the decoration of Neferu's tomb most likely alludes to her duties as a priestess of this goddess.

Relief of a Woman Presenting an Ointment Vessel

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2030-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, temple of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II

Limestone, paint

10 1/4 × 6 1/4 × 1 9/16 in. (26 × 15.9 × 4 cm)

he Metropolitan Museum of Art

Raised relief was used for the facades of the queen’s shrines. This figure of a servant carrying an ointment vessel originally stood behind the queen. Above her is a geometrical pattern reproducing architectural elements originally constructed in wood.

Statue head of Senusret III

Musée de Louxor, (Égypte)

Luxor Museum, Luxor Egypt

Senusret III was a warrior-king, often taking to the field himself. In his sixth year, he re-dredged an Old Kingdom canal around the first cataract to facilitate travel to upper Nubia. He used this to launch a series of brutal campaigns in Nubia in his sixth, eighth, tenth, and sixteenth years. After his victories, Senusret built a series of massive forts throughout the country to establish the formal boundary between Egyptian conquests and unconquered Nubia at Semna.

The personnel of these forts were charged to send frequent reports to the capital on the movements and activities of the local Medjay natives (By the Middle Kingdom, the pastoral nomads were called the Medjay and referred to as an enemy of the people). They worked as dancers, as soldiers, and became a part of Egyptian society., some of which survive, revealing how tightly the Egyptians intended to control the southern border. Medjay were not allowed north of the border by ship, nor could they enter by land with their flocks, but they were permitted to travel to local forts in order to trade.

Relief of Queen Kemsit Seated

Period: Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

Date: ca. 2030-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Temple of Mentuhotep Nebhepetre

Limestone

16 1/8 × 16 1/8 × 5 1/2 in. (41 × 41 × 14 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Queen Kemsit sniffs an ointment jar, while a servant pours liquid into a cup. The queen’s elaborate dress is covered with a pattern of feathers, an embellishment usually reserved for deities and perhaps here related to Kemsit’s role as a Hathor priestess.

After this, Senusret sent one more campaign in his 19th year, but turned back due to abnormally low Nile levels, which endangered his ships. One of Senusret's soldiers also records a campaign into Palestine, perhaps against Shechem, the only reference to a military campaign against a location in Palestine from the entirety of Middle Kingdom literature.

Relief of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II and Queen Kemsit

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2030-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Temple of Mentuhotep Nebhepetre

Limestone

22 7/16 × 20 1/16 × 8 11/16 in. (57 × 51 × 22 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The decoration on the sides of the queens’ shrines was rendered in sunk relief. Here, Kemsit stands behind the king and embraces him. While this gesture of affection is endearing, it symbolized the ritual role of the queen, rather than expressing personal ties. The yellow and black background color imitates wood. Many of the forms of ancient Egyptian stone architecture were derived from constructions made of wood and other perishable materials.

Domestically, Senusret has been given credit for an administrative reform which put more power in the hands of appointees of the central government, instead of regional authorities. Egypt was divided into three waret, or administrative divisions: North, South, and Head of the South.] Each region was administrated by a Reporter, Second Reporter, some kind of council (the Djadjat), and a staff of minor officials and scribes. The power of the Nomarchs seems to drop off permanently during his reign, which has been taken to indicate that the central government had finally suppressed them, though there is no record that Senusret ever took direct action against them.

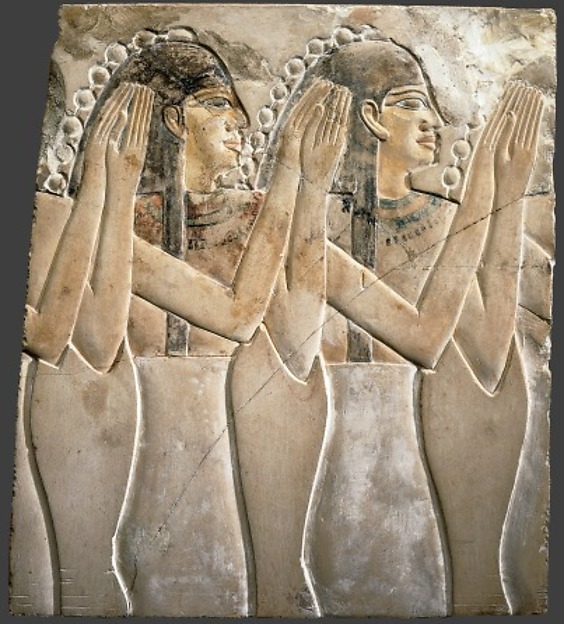

Relief of Wives of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11

Mentuhotep II

ca. 2030-2000 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, temple of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II

Limestone, paint

39 3/4 × 28 15/16 in. (101 × 73.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Relief decoration in the temple of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II shows that royal women of the Eleventh Dynasty played an important role in cult and state ceremonies. The excavators composed this relief from two blocks that belonged to a scene representing a procession of women identified as wives of the king in the accompanying inscriptions. These figures depict Queen Kawit (left) and Queen Kemsit (right) with their right hands on their chests in poses of reverence or respect. The reliefs are carved in the later style of the Mentuhotep era, which was influenced by northern, Memphite art.

Senusret III had a lasting legacy as a warrior Pharaoh. His name was Hellenized by later Greek historians as Sesostris, a name which was then given to a conflation of Senusret and several New Kingdom warrior pharaohs. In Nubia, Senusret was worshiped as a patron God by Egyptian settlers. The duration of his reign remains something of an open question. His son Amenemhet III began reigning after Senusret's 19th regnal year, which has been widely considered Senusret's highest attested date. However, a reference to a year 39 on a fragment found in the construction debris of Senusret's mortuary temple has suggested the possibility of a long coregency with his son.

Head of Pharaoh Mentuhotep II

XI din., Kingdom of Mentuhotep II, 2010-1998 BC

Sandstone yellow.

Height 60 cm

Thebes.

Vatican Museum

Head of a statue in sandstone. Egyptian Pharaoh Mentuhotep Nebtauirá second ruler of the XI Dynasty (2010-1998 BC). The face is painted dark red to represent the color of the skin as a typical convention of Egyptian figurative art. The name of the sovereign is inscribed on the pillar of support behind the right side.

The reign of Amenemhat III was the height of Middle Kingdom economic prosperity. His reign is remarkable for the degree to which Egypt exploited its resources. Mining camps in the Sinai, which had previously been used only by intermittent expeditions, were operated on a semi-permanent basis, as evidenced by the construction of houses, walls, and even local cemeteries.

Statuette head of Amenemhat III

1843 - 1798 avant J.-C. (12e dynastie)

calcaire

1860–1814 BCE (12th Dynasty)

Louvre

There are 25 separate references to mining expeditions in the Sinai, and four to expeditions in wadi Hammamat, one of which had over 2,000 workers. Amenemhet reinforced his father's defenses in Nubia and continued the Faiyum land reclamation system.

Relief of the Goddess Hathor

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Amenemhat III

1859-1813 BC

Egypt, Lisht

Limestone

24 13/16 × 27 3/16 × 2 9/16 in. (63 × 69 × 6.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The goddess Hathor wears a typical headdress with a sun disk enclosed by a pair of cow horns. She lifts a menat necklace from her chest and holds a sistrum, a musical instrument related to her cult. The inscription behind her commemorates King Amenemhat III’s Sed festival, or jubilee. The relief seems to have been part of an addition or repair made by Amenemhat III to the pyramid complex of his ancestor, King Amenemhat I.

Amenemhet IV

12th dynasty of Egypt

After a reign of 45 years, Amenemhet III was succeeded by Amenemhet IV, whose nine-year reign is poorly attested. Clearly by this time, dynastic power began to weaken, for which several explanations have been proposed. Contemporary records of the Nile flood levels indicate that the end of the reign of Amenemhet III was dry, and crop failures may have helped to destabilize the dynasty. Further, Amenemhet III had an inordinately long reign, which tends to create succession problems.

Sobekneferu, "the beauty of Sobek."

Twelfth Dynasty

The latter argument perhaps explains why Amenemhet IV was succeeded by Sobekneferu, the first historically attested female king of Egypt. Sobekneferu ruled no more than four years, and as she apparently had no heirs, when she died the Twelfth Dynasty came to a sudden end as did the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom.

She adopted the full royal titulary, distinguishing herself from prior female rulers. She was also the first ruler to have a name associated with the crocodile god Sobek. Contemporary evidence for her reign is scant: there are a few partial statues – one with her face – and inscriptions that have been uncovered. It is assumed that the Northern Mazghuna pyramid was intended for her, though this assignment is speculative with no firm evidence to confirm it. The monument was abandoned with only the substructure ever completed. A papyrus discovered in Harageh mentions a place called Sekhem Sobekneferu, that may refer to the pyramid. Her rule is attested on several king lists.

Relief with two officials or sons of the Vizier Dagi

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 11

Late reign of Mentuhotep II or later

ca. 2010–2000 B.C. or ca. 2000–1981 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Tomb of Dagi

Limestone, paint

L. 63 cm (24 13/16in.); H. 47.2 cm (18 9/16 in.); D. 7.7 cm (3 1/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dagi was a treasurer and vizier during the late years of Mentuhotep II (2010–2000 B.C.) and the reign of Mentuhotep III (ca. 2000–1988 B.C.). His rock-cut tomb overlooked the Asasif valley (the eastern extension of Deir el-Bahri). Owing to the friable consistency of the rock, the massive pillars had to be strengthened with brick. Both the brick and rock segments of the pillars were covered with plaster and painted with scenes from daily life.

Unusually, the corridor into the interior started from the tomb facade, not from the transverse hall behind the pillars, as was the norm. It led to an interior offering chapel. Both the corridor and the chapel were cased in fine limestone and decorated with painted reliefs. The tomb was used in early Christian times as a monastery, and the casing blocks were, either at that time or earlier, taken down and smashed to pieces. Only a handful of fragments were recovered; the exceptionally fine relief forms a convincing link in the stylistic development from the earlier reliefs of the tomb of Khety to later reliefs from Lisht North.

Here two exquisitely adorned and made-up young men are squatting, each with one knee up. Their attitude is reverential, with their left hands on their right shoulders and their right hands gripping their left forearms.The preserved hieroglyphs read Saiset (Son of Isis), an early example of the use of the goddess Isis in a name. It is unclear whether these two men are sons of the tomb owner or high officials who served in his court. More on Vizier Dagi

Stela of the Overseer of the Western Desert Kay

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Early Dynasty 12

ca. 1981–1919 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Kamala, W of Luxor

Limestone

H. 67 cm (26 3/8 in.); W. 34 cm (13 3/8 in.); D. 9 cm (3 9/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The standing figures depicted here are Kay, overseer of the Western Desert and of hunters of the desert districts, and a woman who was either his wife or mother. The texts relate that Kay was "the best of the troops on a day of difficulty" and describe a trip to a western oasis during which he investigated desert roads and apprehended a fugitive. His five dogs of different breeds are individually designated with a name or number.

Head of a statue, thought to represent Sekhemre Khutawy Sobekhotep, although other attributions have been proposed

Louvre Museum

After the death of Sobeknefru, the throne may have passed to Sekhemre Khutawy Sobekhotep, though in older studies Wegaf, who had previously been the Great Overseer of Troops, was thought to have reigned next. Beginning with this reign, Egypt was ruled by a series of ephemeral kings for about ten to fifteen years. Ancient Egyptian sources regard these as the first kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty, though the term dynasty is misleading, as most kings of the thirteenth dynasty were not related. The names of these short-lived kings are attested on a few monuments and Graffiti, and their succession order is only known from the Turin Canon, although even this is not fully trusted.

Stela of the Steward Mentuwoser

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12

Reign of Senwosret I, year 17

ca. 1944 B.C.

Egypt, Northern Upper Egypt, Abydos

Limestone, paint

H. 103 cm (40 9/16 in.); W. 50.5 cm (19 7/8 in.); Th. 8.3 cm (3 1/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This rectangular stone stela honors an official named Mentuwoser. Clasping a piece of folded linen in his left hand, he sits at his funeral banquet, ensuring that he will always receive food offerings and that his family will honor and remember him forever. To the right of Mentuwoser, his son summons his spirit. His daughter holds a lotus, and his father offers a covered dish of food and a jug that, given its shape, contained beer.

To show clearly each kind of food being offered, the sculptor arranged the images on top of the table vertically. The feast consists of round and conical loaves of bread, ribs and a hindquarter of beef, a squash, onions in a basket, a lotus blossom, and leeks. The low-relief carving is very fine. The background was cut away only about one-eighth of an inch. Within the firm, clear outlines, the sculptor then subtly modeled the muscles of Mentuwoser's arms and legs and the shape of his jaw and cheeks. The chair legs and the calf's head have also been carefully formed. The hieroglyphic inscriptions in sunk relief state that in the seventeenth year of his reign King Senwosret I presented the stela to Mentuwoser in appreciation of his loyal services. Mentuwoser's deeds are described at length. He was steward, granary official, and overseer of all manner of domestic animals, including pigs. He is described as a good man who looked after the poor and buried the dead. Senwosret's throne name, Kheperkare, appears within a cartouche in the middle of the top line.

The stela once stood at Abydos, the sacred pilgrimage center of the god of the underworld Osiris. Mentuwoser's image and the prayers on the stela were meant to bring him both rebirth and sustenance at the annual festivals honoring Osiris. At such festivals family members and other pilgrims would visit the commemorative chapels in which the stelae were set up, and at its end this stea's text addresses explicitly three groups of people: 1. any scribe who shall read the stela; 2. any person who shall hear the stela read aloud; 3. all people who shall approach it. It is thus suggested that, according to ancient Egyptian understanding, the written word—and its imagery—reached many more people than only just the fully literate.

Figurine of a Nude Female

Middle Kingdom, Date: ca. 2030-1640 B.C.

Egypt

Faience, fine tin-glazed pottery

H. 13.7 cm (5 3/8 in.); W. 4.7 cm (1 7/8 in.); D. 2.8 cm (1 1/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

New types of figurines appeared during the Middle Kingdom depicting women with elaborate hairstyles who are either nude or wear garments that accentuate female anatomy. They have abbreviated limbs, wear jewelry, and are often tattooed. One type is formed from flat pieces of wood, the other from faience. Previously, they were described as concubines for the dead and more recently as sacred dancers tied to the cult of Hathor, though the absence of legs remains puzzling.

Khasekhemre Neferhotep I

Reign of Neferhotep I (around 1740 BCE), 13th dynasty, Middle Kingdom

Egypt, Faiyum.

Archeological Museum of Bologna (Italy)

After the initial dynastic chaos, a series of longer reigning, better attested kings ruled for about fifty to eighty years. The strongest king of this period, Neferhotep I, ruled for eleven years and maintained effective control of Upper Egypt, Nubia, and the Delta, with the possible exceptions of Xois (modern-day Sakha) and Avaris (Tell el-Dab'a). Neferhotep I was even recognized as the suzerain of the ruler of Byblos, indicating that the Thirteenth Dynasty was able to retain much of the power of the Twelfth Dynasty, at least up to his reign

Head of a Statue of a Queen or Princess as a Sphinx

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

ca. 1981-1802 B.C.

Egypt; Probably from Heliopolis

Chlorite

H. 38.9 cm (15 5/16 in.); W. 33.3 cm (13 1/8 in.); D. 35.4 cm (13 15/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Judging from the remains of the animal’s body at the back, this spectacular head was part of a large female sphinx with the face of a queen or princess. Combining the head of a king or royal woman with the body of a lion, sphinxes seem to have functioned as guardian figures. Female sphinxes likely existed in the Old Kingdom but were more prevalent in the Middle Kingdom, perhaps reflecting changing ideas about queenship. The head has a fascinating history. Possibly found in the villa of the Roman emperor Hadrian at Tivoli, it was once in the collection of Cardinal Alessandro Albani (1692–1779), who likely commissioned the restoration of the chin, mouth, and eyes, the latter of which originally held inlays.

Sobekhotep IV

Temple of Amun, Karnak, Pylon VII

Louvre

Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV was one of the more powerful Egyptian kings of the 13th Dynasty, who reigned at least eight years. His brothers, Neferhotep I and Sihathor, were his predecessors on the throne, the latter having only ruled as coregent for a few months.

Sobekhotep states on a stela found in the Amun temple at Karnak that he was born in Thebes. He is known by a relatively high number of monuments, including stelae, statues, many seals and other minor objects. There are attestations for building works at Abydos and Karnak.

At some point during the 13th dynasty, Xois and Avaris began governing themselves, the rulers of Xois being the Fourteenth Dynasty, and the Asiatic rulers of Avaris being the Hyksos of the Fifteenth Dynasty. According to Manetho, this latter revolt occurred during the reign of Neferhotep's successor, Sobekhotep IV, though there is no archaeological evidence

Head of a Statue of a Queen as a Sphinx

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Mid Dynasty 12

ca. 1919-1878 B.C.

Egypt; Said to be from Heliopolis

Quartzite

H. 27 cm (10 5/8 in.); W. 24 cm (9 7/16 in.); D. 22 cm (8 11/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The uraeus on this lifesize head leaves little doubt that a queen or princess is represented; the narrow shoulders and their continuation in the back make it clear that she is from a sphinx, a composite creature combining a lion’s body and a human head. In the Middle Kingdom, royal women began to be depicted as sphinxes, a statue type previously usually reserved for the king. The overall shape of the face, the modeling, and the form of the eyes indicate that the head likely dates to the reign of Senwosret II.

Statue of Senwosret I Kneeling

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, Senwosret I, ca. 1961-1917 B.C.

Egypt, Memphite Region, Memphis

Gneiss

H. 48 cm (18 7/8 in.); W. 27.5 cm (10 13/16 in.); D. 17.5 cm (6 7/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Middle Kingdom royal statuary frequently depicted the king performing acts of worship. The kneeling pose of a pharaoh holding offering vessels, here missing, was first introduced during the Old Kingdom. Most of these earlier works were small and thus could be handled during ritual performances. This statue is too large for easy movement and was presumably placed near a deity shrine, where it eternalized the king’s act of worship.

Colossal Head of Senwosret I

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, Senwosret I, ca. 1961-1917 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Karnak

Limestone, paint

28 3/4 × 13 3/8 × 19 11/16 in. (73 × 34 × 50 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This head was once part of a mummiform statue of the king wrapped in a linen shroud and holding large ankh (life) amulets in his crossed hands. Over 10 feet high, the statue was one of a group representing Senwosret I as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. Lined up either along the approach to the temple or to the sides of an entrance, the statues marked and guarded the transition from the outside world to a sacred interior. The king wears the double crown, which generally signifies both parts of the country

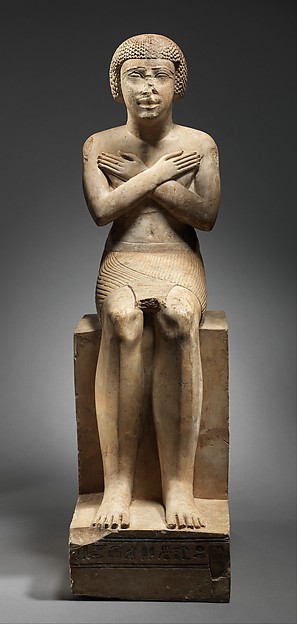

Statue of the Steward Meri Seated

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11, ca. 2124-1981 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes

Limestone

21 7/8 × 6 1/4 × 10 13/16 in. (55.5 × 15.8 × 27.4 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This statue is a three-dimensional example of the style known from reliefs of the early reign of Mentuhotep II. Based on their similarity to a hieroglyph for “assemble,” the crossed arms may have a funerary meaning, perhaps expressing the confidence that Meri’s body would be made whole again and thus ready for eternal life. The statue likely originates from a tomb in western Thebes.

Upper Part of a Royal Statue Seated

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Senwosret II, Date: ca. 1887-1878 B.C.

Egypt; Said to be from Memphite Region, Memphis

Granodiorite

H. 34 cm (13 3/8 in.); W. 24.8 cm (9 3/4 in.); D. 14.7 cm (5 13/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Historical records from the reigns of Amenemhat II and Senwosret II are scarce, and many artworks likely from these reigns lack inscriptions. It is clear, however, that significant artistic changes took place during this time. Faces have shed the abstract idealization of earlier works. The facial musculature is softly articulated, rounded eyes press against fleshy lids, and the mouth has lost its rigid edge. The face is not yet personalized, but it has come alive.

Head of a Colossal Statue of Senwosret III

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Senwosret III

ca. 1878-1840 B.C.

Egypt

Quartzite

17 3/4 × 13 1/2 × 17 in. (45.1 × 34.3 × 43.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

During the mid-Twelfth Dynasty, the face of the pharaoh underwent a startling transformation from that of a youthful, idealized monarch to a mature individual, with soft folds of sagging flesh, prominent bone structure, and protruding eyes, all of which are reflected in this imposing, monumental work. These changes must have resulted from new ideas about kingship, perhaps here manifested as a desire to depict a king who has gained the wisdom to lead Egypt.

Head of a Statue of Amenemhat III Wearing the White Crown

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Amenemhat III

ca. 1859-1813 B.C.

Egypt

Greywacke

H. 46 cm (18 1/8 in.); W. 18.5 cm (7 5/16 in.); D. 25.5 cm (10 1/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A masterpiece of ancient Egyptian sculpture, this head depicts Amenemhat III so arrestingly that the viewer is left with the indelible impression that it represents the king’s actual appearance. Nothing is known, however, of this ruler’s true physiognomy. The sculptor has so masterfully suggested skin and soft flesh in the velvety texture of the stone that any sense of hardness dissolves. It contrasts with the firm, polished surface of the white crown, a symbol of Upper Egypt.

Head of a Statue of Amenemhat III

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty: Dynasty 12

Amenemhat III

ca. 1859-1813 B.C.

Egypt, Aswan

Granodiorite

H. 11.6 cm (4 9/16 in.); W. 14.3 cm (5 5/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fragments of the body found with this head indicate that the complete statue was seated, likely one of the modestly sized royal sculptures donated to Egyptian temples by Middle Kingdom kings. Amenemhat III here wears a nemes headdress, a folded and pleated piece of cloth generally reserved for the pharaoh. The head is made of a type of limestone rarely used in ancient Egyptian artworks.

A scarab of Wahibre Ibiau

Petrie Museum

Wahibre Ibiau (throne name: Wahibre; birth name: Ibiau) was an Egyptian king of the 13th Dynasty, who reigned ca. 1670 BC for 10 years 8 months and 29 days . Despite a relatively long reign for the period, Wahibre Ibiau is known from only a few objects. Wahibre is mostly attested by scarab seals bearing his name. He is also named on the stela of an official named Sahathor, probably from Thebes. Finally, a fragment of fayence from El-Lahun mentions this king.

A notable member of Ibiau's royal court was the namesake vizier Ibiaw. It has been suggested that this vizier could have been the same person of Ibiau earlier in his life.

Sobekhotep IV was succeeded by the short reign of Sobekhotep V, who was followed by Wahibre Ibiau, then Merneferre Ai. Wahibre Ibiau ruled ten years, and Merneferre Ai ruled for twenty three years, the longest of any Thirteenth Dynasty king, but neither of these two kings left as many attestations as either Neferhotep or Sobekhotep IV. Despite this, they both seem to have held at least parts of lower Egypt. After Merneferre Ai, however, no king left his name on any object found outside the south. This begins the final portion of the thirteenth dynasty, when southern kings continue to reign over Upper Egypt, but when the unity of Egypt fully disintegrated, the Middle Kingdom gave way to the Second Intermediate Period.

Pharaoh Merneferre Ay on a boat, ministering before the god Horus

Scene from his pyramidion

13th dynasty

Originally from Memphis, but found in Khatana. Now, Cairo

Egyptian Museum

Merneferre Ai (also spelled Ay) was the longest reigning pharaoh of the 13th Dynasty, he ruled a fragmented Egypt for over 23 years in the early to mid 17th century BC. A pyramidion bearing his name shows that he possibly completed a pyramid, probably located in the necropolis of Memphis.

Merneferre Ai is the last pharaoh of the 13th dynasty to be attested outside Upper Egypt and in spite of his long reign the number of artefacts attributable to him is comparatively small. This may point to problems in Egypt at the time and indeed, by the end of his reign, "the administration [of the Egyptian state] seems to have completely collapsed". It is possible that the capital of Egypt since the early Middle Kingdom, Itjtawy was abandoned during or shortly after Ay's reign. For this reason, some scholars consider Merneferre Ay to be the last pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

Acknowledgement: Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom - Metropolitan Museum, Wikipedia,

No comments:

Post a Comment